Think Twice

A fever dream about Bob Dylan

People who are continuing paid subscription, you are making me verklempt. New subscribers are making me verklempt. In year two, I’m thinking about how to make you happy. What a great job.

By the way, I’ve received a number of wonderful messages from paid subscribers, but there’s no way on the platform to answer your notes. I have read them all and love them.

Zoom conversation #3 on writing MEMOIR is on SEPTEMBER 23 at 3-4pm EST. It’s free for paid subscribers, and there will be more events planned, plus we’ll record this one for paid subscribers as well. to RSVP: email me: lauriestone@substack.com.

This stack post is about changing your mind and letting people be what they are. Not my strong suits, but hey.

There are three buttons at the bottom of each post: “like,” “share,” and “comment.” I love hearing from you, and your reactions attract new subscribers. Thanks!

Please, if you are able to jump in with a paid subscription, you’ll be keeping the publication afloat. I’ll never put up a paywall for reading posts. Your generosity makes this work.

Think Twice

Every fight Richard and I have had is basically about Bob Dylan. Not because Richard loves Dylan so much. It’s because I want Richard to sense the world through my body and not his own. What a little prick I am for wanting that. What a nerve to want that of anyone, yet I go back to wanting it.

When Richard looks at Dylan, there’s space in his heart to consider Dylan’s jaunty tunes, and his survey of the American songbook, and the fact that musicians like recording with him. When I look at Dylan, I see a man who has never made a woman real in a song. The women in Dylan’s songs have no thoughts and feelings of their own. They’re there to listen, and if they’re imagined at all, they’re imagined caring about how the singer feels. When I listen to a Dylan song, I imagine what I would say if a man said these things to me. I have a good time.

Dylan:

You used to be so amused

At Napoleon in rags and the language that he used

Go to him he calls you, you can't refuse

Laurie:

Yes, I can. And fuck you.

Dylan:

Lay, lady, lay

Lay across my big brass bed

Laurie:

No.

Dylan (“Don't Fall Apart on me, Tonight,” 1983, included in “Infidels”):

Don't fall apart on me tonight

I just don't think that I could handle it

Don't fall apart on me tonight

Yesterday's just a memory

Tomorrow is never what it's supposed to be

And I need you, yeah

Laurie:

Really, you need me? What for? Also, I find this really confusing: You are asking me not to fall apart because then it will make you fall apart because you can't handle it? Shouldn't the title be, like, you saying, “I hope I don't fall apart tonight”? Okay, whatever.

Dylan:

Come over here from over there, girl

Sit down here, you can have my chair

I can't see us goin' anywhere, girl

The only place open is a thousand miles away, and I can't take you there

Laurie:

Okay, first, I don't want your chair. And why are you telling me you can't see us going anywhere? After that line, like I'm supposed to care about anything else you say? Are you kidding me? And by the way, if I want to get to the open place a thousand miles away, what makes you think I need you to take me there, boy? I got legs. I got a car.

Dylan:

I wish that I'd been a doctor

Maybe I'd have saved some life that had been lost

Maybe I'd have done some good in the world

'Stead of burning every bridge I crossed

Laurie:

Why are you telling me this? I don't care. Go feel sorry for yourself a thousand miles away. Here, take my car keys.

Dylan:

I ain't too good at conversation, girl

So you might not know exactly how I feel

But if I could, I'd bring you to the mountaintop, girl

And build you a house made out of stainless steel

Laurie:

First, yes, you are terrible at conversation. Two, I don't care how you feel. Honestly, I don’t. Three, why would I want to go to a mountaintop with you? How do you see us getting there? Then I'd be stuck in a stainless steel kitchen, on a mountain, alone? Oh, great, sign me up.

Dylan:

But it's like I'm stuck inside a painting

That's hanging in the Louvre

My throat start to tickle and my nose itches

But I know that I can't move

Laurie:

I don't care.

Dylan:

Who are these people who are walking towards you?

Do you know them or will there be a fight?

With their humorless smiles so easy to see through

Can they tell you what's wrong from what's right?

Laurie:

Okay, so, you think I look to other people to form my moral understandings? You are an idiot.

Dylan:

Oh, do you remember St. James Street

Where you blew Jackie P's mind?

You were so fine, Clark Gable would have fell at your feet

And laid his life on the line

Laurie:

Clark Gable? What century are you living in? Also it's "fallen," not "fell."

And now, can you please stop wasting my precious time?

If Richard were talking to you, he’d say, “Of course I see this side of Dylan.” Honestly, I don’t know what we’re fighting about when we fight. Richard would also say to me: “You just like to fight.” And who could argue with that?

Yesterday, we’re driving to the city from Hudson, so I can have my teeth cleaned. I love my dental hygienist. Richard doesn’t have to go, but he wants to make life easier for me, what a mensch, and driving together is like walking together—side by side as the world floats by. I’m trying to be generous in return, and I look for a song I recently heard Dylan sing I really liked, except I can’t remember it and I wind up playing, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” written in 1962 when Dylan is twenty. He’s twenty, and already he’s got so much to sneer about.

We’re listening to the song, and suddenly I hear it differently. When the narrator says to the woman, “Don’t think twice,” he doesn’t mean it. He’s saying the opposite of what he’s feeling. He’s actually asking her to think twice, and now the song has gotten me to think twice, and I love it. Few things serve a writer better than being wrong, and often I’m wrong because—very much in the style of pissed-off Bobby Zimmerman—I’m a stubborn little prick.

Here are the lyrics:

It ain't no use to sit and wonder why, babe

If'n you don't know by now

And it ain't no use to sit and wonder why, babe

It'll never do somehow

When your rooster crows at the break of dawn

Look out your window and I'll be gone

You're the reason I'm a-traveling on

But don't think twice, it's all right

And it ain't no use in turning on your light, babe

That light I never knowed

And it ain't no use in turning on your light, babe

I'm on the dark side of the road

But I wish there was somethin' you would do or say

To try and make me change my mind and stay

But we never did too much talking anyway

But don't think twice, it's all right

So it ain't no use in calling out my name, gal

Like you never done before

And it ain't no use in calling out my name, gal

I can't hear you anymore

I'm a-thinking and a-wonderin' walking down the road

I once loved a woman, a child, I'm told

I give her my heart but she wanted my soul

But don't think twice, it's all right

So long honey, babe

Where I'm bound, I can't tell

Goodbye's too good a word, babe

So I'll just say, "Fare thee well"

I ain't a-saying you treated me unkind

You could've done better but I don't mind

You just kinda wasted my precious time

But don't think twice, it's all right

In the past when I’d heard the song, I thought it was the same old, you can’t have me, babe, you can’t pin me down rambler song he and so many other fools have sung over and over for reasons I will never know. Like anyone, even other men, need to know this? This time, in the car, I heard a guy trying to buck himself up after he’s been shown the door, more or less, or he’s read the writing on the wall that says, “Okay, buddy, time to pack up.”

When the singer says, “I ain’t a-saying you treated me unkind/You could’ve done better but I don’t mind,” he’s feeling vulnerable, although the schmendrick can’t come right out and say it. When he says, “But I wish there was somethin’ you could do or say/To try and make me change my mind and stay/But we never did too much talking anyway/But don’t think twice it’s all right,” he’s wanting her to pull him toward her. What he would do after that, we don’t know, but in that moment, he doesn’t want to be let go of so easily.

Richard said, “The singer is not only asking the woman to think twice. The whole song is about thinking twice. He’s asking himself what happened in the relationship and what he really feels in the moment of setting off.” I said, “I can see that. I can see he’s hurt and defensive, although he still has to sound like he’s telling her off. The song is still all about the boy’s thoughts. The girl is a ghost. That’s the part that sucks out any possible compassion for him.” Richard said, “He may not want compassion from anyone.”

What do people see in Bobby, who doesn’t seem to want anything from us? On stage, he brilliantly enacts three principles I believe art needs: Don’t justify yourself, don’t make apologies for who and what you are, and don’t ask for love. Bobby doesn’t need to make women real in his songs to suit me. Richard doesn’t need to sense the world through my understandings. Yet here we are, rubbing each other in this brilliant tide of being, tumbling along.

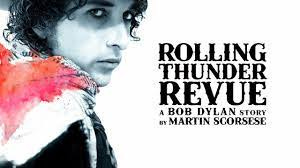

A few years ago, I jotted down notes after watching several docs about Dylan: Trouble No More–A Musical Film (2017) and Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story By Martin Scorsese. I was trying to think about what women could learn from Bobby rather than sit next to him in a bar.

Here are the notes:

Slack armed intellectuals with baggy pants would rather be Bob than get the girl. Bob is close to being the girl, himself, in the early days with his cloud of curls, thin shoulders, and hips that aren’t there. He’s elfin, wolfish, furrowed, pulling on a smoke, collar up, hunched against alleyway chills. Long eyelashes and a smooth, bar mitzvah face. Yet there is already something dead in the eyes.

At nineteen, he arrives in New York and starts sponging up the phrasings and picking of other musicians. The dead thing in his eyes is what makes him butch, and you can see from his body how any girl can be butch if she doesn’t ask for things or move too smoothly in her joints.

Bob sings for other men. In the early days, he sniffs around men for what they can do for him. There are women in some of the pictures, but he’s not looking at the women. He’s looking inward, as if the camera could snatch away something essential. He had a habit: Whatever worked for him, he didn’t give it away. Has ever a performer made less of an offering to the audience? I don’t mean the quality of his work. I mean his sense of giving them something. Dylan is: I have to do this. This is what I do. I can’t help it. I do it all the time. You can watch me do it. Take it or leave it. I’m going to do it, anyway.

“Remember, Bob,” one of the Clancy Brothers told him early on, “no fear, no envy, no meanness.” That may have been like saying to him: no dreams, no childhood, no scars. Dylan is not a place to go to if you are hungry, yet everyone wants him because of that.

Haven’t we all, at some time, wanted to ride a motorcycle into our first death and smell like a hundred nights in the same jeans? Don’t we want to stare blankly and sarcastically at questions about who we are and what we mean? We want to smoke and not smile. We want to turn our backs and become a metal door. Nothing is cooler than not asking for approval. Getting it done, leaving behind what must be left behind. Nothing is cooler than being willing to let everything fall away, including your youth and stamina, and still keep making art.

Dylan’s music laughs. If you want to hear it that way, it can laugh at the irritability and pomposity of the lyrics. The music is jazzy, jangly, bluesy, rough hewn, electric, and stirring. He became a master of melody—think “Tangled up in Blue,” “All Along the Watchtower,” “Forever Young,” “If Not for You,” and “Knocking on Heaven’s Door.” The voice is a snarl and a whine. It’s twangy and davening—insistent, ferrety, seeping—the not-beautiful thing we can connect to. When Bob first heard the music that would point him away from where he came from, it made him feel like maybe he was born to the wrong parents, that he was someplace far from his real home and the errand of his life was to get himself back to that place.

The thing for women to steal from Dylan is the energy to get where you need to get to. To keep working, against all odds. You have to trust it. Just don’t date him or become road kill under his wheels.

oh-my-god, this is fan-fuckin-tastic. You have got his number, babe. And I love your talking back to that "schmendrick." Haven't heard that word in eons.

Honestly, I think he stole that energy from women in the first place.