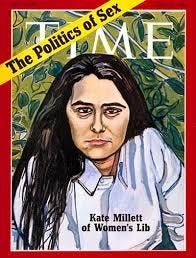

Last week, a young man came to the house to talk with me about Kate Millett. He’s doing research on her life and the comet of the women’s movement, streaking across the skies in the 1960s and early 1970s. He asked me …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Everything is Personal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.