Janet Malcolm

A last laugh.

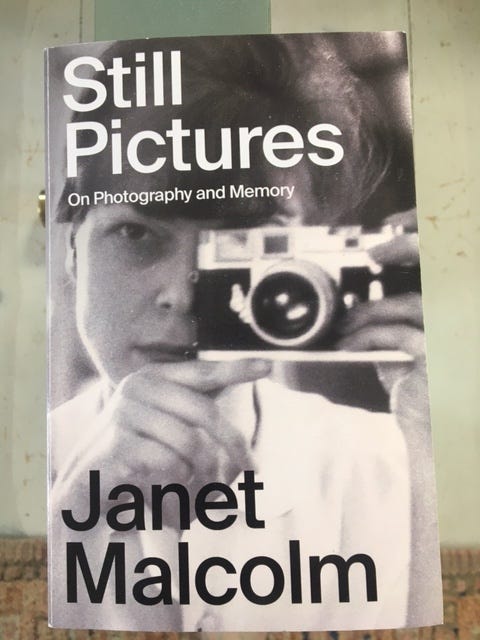

On Still Pictures, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023.

No one knows why they remember anything. The details of a disaster—like the time you were taken hostage or the time your house was flattened by a tornado—may blur, while you can still describe the insignia on a button you saw when you were four. As Janet Malcolm puts it in her posthumous memoir, Still Pictures, On Photography and Memory, “The past is a country that issues no visas. You can only enter it illegally.” Malcolm died of lung cancer in 2021 at the age of 86.

She left behind a gorgeous book and a weird book, and as you read it, you don’t know why she decided to write about this seemingly trivial moment when she was growing up or why she resurrects that couple rather than a different couple among her parents’ circle of Czech Jews who had escaped from Hitler. You don’t care why. According to the story, Malcolm’s family was able to leave Prague in 1939 by bribing an SS officer with enough money for him to buy a racehorse.

Still Pictures is arranged as a series of prompts from photos that look grainy or unexceptional in ways other than their meaning to Malcolm. They are windows she looks through and doors she passes through to find herself drawn, again and again, to the clothes, the food, and the housing arrangements of these dislocated Jews, saved from death and sprung loose from a Europe where they were young and chic. In New York, where Malcolm’s family settles, they are modest and bourgeois—her father is a doctor. They are modest and bougeois as a way to fit into their new world.

The book’s memories are congenial, even when offered, like a piece of apple, at the end of a knife. In many of Malcolm’s books—In the Freud Archive, The Journalist and the Murderer, and The Silent Woman among them—the Malcolm narrator is a jackel on the hunt for some kind of fakeness, some kind of grandstanding, some kind of self-promoting flamboyance, some kind of cry-baby blaming of other people for the subject’s mess. In her final book, she doesn’t want to dislike anything. She wants to find pleasure, and the pleasure she finds is mainly in the way she uses language. As you follow her thoughts, you find less a world you can clip together from the fragments she lays out than the witty narrator, herself, who has been gentled in some way and finds herself amused by life. As she’s about the leave it.

There are dozens of other passages I could have picked out that are as moving, or sharp, or funny, or reflective of the world Malcolm grew up as the ones I’ve gathered here. Malcolm writes in two time frames, lending the book its coherence and intimacy. The narrator is looking back and trying to evoke the feelings and thoughts of the creature she once was, and at the same time the narrator is conveying how the memories are making her feel now, in the moment of talking to us. She’s giving us thought-in-action.

About her first vivid memory, in fourth grade, she writes: “A classmate named Jean Rogers slid into a seat next to me and asked if I would be her best friend. Until this time, I had no friends. What Jean Rogers said made me happier than perhaps I had ever been. That her overture had been completely unexpected and unsolicited only heightened its powerful effect on me.”

Conjuring the movie Casablanca, she joins the chorus of women who for decades have screamed at Ingrid Bergman, “Don’t ditch Bogie, are you nuts?”: “Do you remember the noble Czech resistance leader played by Paul Henreid? That this paragon was Czech rather than Polish or Hungarian or from any other Nazi-occupied country is a reflection of the high regard in which Czechoslovakia was held in the Allied World of 1942. Today, no one in their right mind can stand this self-satisfied sap or understand why Ingrid Bergman chooses him over Humphrey Bogart. It is to my credit and to my sister’s that we couldn’t stand most of the Czechs in our parents’ circle of émigrés.”

On Malcolm’s sense of yearning: “. . . the habit we form in childhood, the virus of lovesickness that lodges itself within us, for which there is no vaccine. We never rid ourselves of the disease. We move in and out of states of chronic longing. When we look at our lives and notice what we are consistently, helplessly gripped by, what else can we say but ‘me too.’”

On a girl crush she has in her teens: “When I say I was in love with her, I am speaking from later knowledge. At the time—the late nineteen-forties—girls in love with other girls didn’t recognize what was staring them in the face. They—we—thought you could be in love only with boys. Lesbianism was something you only heard about. There was a book called The Well of Loneliness, a forbidden, rather boring text, from which we formed the idea of lesbians as unhappy, jodhpur-wearing daughters of fathers who had wanted sons.”

In 2007, Malcolm published Two Lives, Gertrude and Alice, a book about Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas. Gertrude and Alice are vague about how they survived the war in France. They misplace their Jewishness when it’s convenient and, in Toklas’ case, her Jew-for-Jesus conversion to Catholicism in the 1950s (with the hope of meeting Stein again in heaven, don’t ask). Anyway, from all this, you would think that Malcolm, the slayer of liars, would have found cause to hunt for blood. But a funny thing happens to her on the way to the kill: she falls in love with Stein and with Stein’s powers of self-invention.

Up to this time, Malcolm has been in the habit of ranking forms of art as if they were members of a feudal society, with imaginative fiction and painting as the lords of the manor and journalism, photography, and biography as the serfs harnessed to plows or begging around the gates. In the company of Stein, these categories begin to lose their sharp edges for Malcolm. The combination of pluck, courage, and luck in Stein’s story excites Malcolm. She marvels at the freedom Stein rips open for language, detaching it from lockstep syntax and determinacy. She cheers the naked appetite of Stein’s self-celebration, especially in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, where, Malcolm says, Stein subverted the whole enterprise of autobiography by “dispensing with the fiction of humility” and rejecting what Malcolm calls “the flaccid narrativity of biography” in favor of “the bracing storylessness of human life.”

By “the bracing storylessness of human life,” Malcolm means plot. She means the defiance of teleological readings of a life, where because a person has moved in a certain direction, you look back retrospectively to see a pattern of causes that were more or less inevitable—and as if destined. It’s as if, for Still Pictures, Malcolm has adopted Stein’s ethos, seeing memory not as a key to unlocking a life but as a bunch of associations that grow around a backward glance without anyone having planted the seeds. She understands the great juice readers are after is not available in an account that has been tightly structured but rather in the beauty of jump cuts and collages that produce pops of connection inside us, the readers, as we follow along.

Toward the end of the Still Pictures, Malcolm tells a rather shaggy-dog story about an actual dog that figured in her life and in the life of her daughter when she was a very young child. Janet and her daughter Anne are remembering visits to Malcolm’s parents in the country, in the 1960s. The dog belonged to friends of Malcolm’s parents and had been trained to charge gleefully up to anyone who whistled a particular tune. Anne had loved seeing the dog bound down a path to greet her. Malcolm writes, “After telling the story, Anne whistled the tune herself—amazingly, it had remained in her memory all these years—and I immediately recognized it as the theme of Antonín Dvořák’s Slavanic Dances. The piece, an orchestral suite, is regularly played on WQXR, and I listen to it with mild boredom verging on irritation. But Anne’s whistling of the theme flooded me with emotion. I can’t exactly account for it—it seemed to act on me as it acted on the dog. It was as if the fifty-year-old ghosts of my parents, my child, and myself were calling to me from the shores of Lost Lake and I was helplessly responding.”

In everyone’s life there is a dog whistle, but in each of us the run back is to a different place. A few chapters later, it hit me where Malcolm was running and perhaps why, and I will tell you my theory, although I dislike theory, especially the kind I am about to propose, which has a psychoanalytic tinge to it. More than a tinge, to be honest. I dislike what I find reductive in psychoanalytic theories, despite the comic tug on us at all times of our unconscious life and the ways it will surface at odd and inconvenient times, like the groundhog that it is.

Before I tell you my theory, I need to tell you about the sudden appearance in Still Pictures of a long and detailed chapter concerning what is probably the most painful and taxing episode in Malcolm’s life: the 10 year period she spent tied up in a libel suit brought against her by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, the subject of In the Freud Archives (1984). Masson claimed that a number of damning things Malcolm quoted him saying in her book were invented by her and did not come from his mouth. There were five passages in contention, and Malcolm had misplaced the notebook where she’d written down these statements. She’d taken notes by hand because she’d dropped and broken her tape recorder at the time of the interview. I will cut to one chase and tell you that, many years after the two trials that took place charging Malcolm with libel, Malcolm’s granddaughter pulled down a red book from a bookcase, and in it were the lost, handwritten notes. However, none of this evidence, which would have ended the law suits, was available at the time of the trials.

Malcolm lost the first trial in 1993, although it was declared a mistrial because the jury was deadlocked in determining an amount Malcolm should pay Masson in damages—their views ranged from millions of dollars to nothing, and one juror suggested one dollar. There was a second trial a year later, and this time Malcolm won, and the chapter in Still Pictures is about how she pulled it off. She hired a speech coach, who transformed her into a person the jurors would like and therefore believe.

Malcolm writes with delicious enjoyment about how, being a member of The New Yorker corps (cult?), with its distanced stance from the scrappy dealings of the world and its tone of patrician reserve, completely fucked up her appearance in court during the first trial. She writes: “I was part of the culture of The New Yorker of the old days—the days of William Shawn’s editorship—when the world outside the wonderful academy we happy few inhabited was only there for us to delight and instruct, never to stoop to persuade or influence in our favor.” Masson’s lawyer wipes the floor with this approach, and the jury, as of course anyone would who is not one of “the happy few,” hates her.

She hires Sam Chwat for the transformation from “defensive loser” to the winner she will become. He advises that she jettison her usual wardrobe of tweeds and somber colors and try to enliven the jurors with bright scarves and a new, colorful outfit each day. Most importantly, he teaches her to fight for herself. Her legal team guesses right that Masson’s lawyer will ask her the same questions as he did in the first trial, and this time she’s prepared to talk a mile a minute, charging toward the points she wants to make, and to direct her testimony directly to the jurors, over the head and shoulders of her cross examiner. Thanking Chwat near the end of the chapter, she writes, “His unspoken but evident distaste for The New Yorker posture of indifference to what others think and his gentle correction of my self-presentation at trial from unpreposessing sullenness to appealing persuasiveness took me to unexpected places of self-knowledge and knowledge of life.”

Where does it take her? It takes her to Gertrude Stein, you could say, or if you don’t want to say it, I will say it. It takes her to what she wrote about Stein “dispensing with the fiction of humility.” Where could such an idea have formed if not from her own experience of the same thing at her second trial? Well, plenty of places, but allow me to connect these elements in her story. When she writes about Stein, another funny thing happens to her for a Shawn-inflected writer for The New Yorker. She drops hints to the reader about the personal stakes in her appreciation of Stein, establishing her Jewishness by inserting untranslated Yiddish words such as meshugenah and goyim into her text and painting a thumbnail of her young self in New York as a peevish, affected creature looking to sting something.

When I read the chapter on Sam Chwat, who was a very famous Henry Higgins to multitudes of movie stars, wanting to shave their Brooklyn accents or acquire them for a part, and who was eulogized after his death in, among other places, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, the shape of Malcolm’s book came flying up to me like a whistled-for dog. Sam had spoken to Janet Jew to Jew. What style in the world could encapsulate goyish more than Shawn’s reserved, bemused, unruffled gestalt? Sam had given Janet back her Jew, and in her last book she wrote not about herself but about the Jews who had made her, the Jews she wanted to hold against herself, the Jews like her parents, her sister, and her younger self who had “escaped the fate of the rest by sheer dumb luck, as a few random insects escape a poison spray.” In this book, Malcolm wanted more than anything to spend time with the people who made her feel things that can go to sleep until they are suddenly recalled to life.

_______________________________________

Support

If this is the day you can take a turn at becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER, please enjoy this season’s discount and a goody bag of benefits, including the next Zoom conversation with guest artist, the great writer and performer David Cale, fresh from his hit run in his latest solo show Blue Cowboy, on Saturday November 29 from 3 to 4 EST. You will be making this stack possible to continue. You will be encouraging literary writing and feminist thought.

______________________________________

Prompty people

“I needed a drink, I needed a lot of life insurance, I needed a vacation, I needed a home in the country. What I had was a coat, a hat and a gun. I put them on and went out of the room.” —Raymond Chandler

Create a narrator who needs four things and instead has three things. Name them. Allow each to become a baby prompt about “needing” and “having.” What happens when the narrator “goes out of the room”?

THIS IS FOR YOUR PLEASURE ALONE. PLEASE DON’T POST YOUR WRITES IN THE COMMENTS BELOW. ENJOY!

_____________________________________

Ex-wives club

From time to time, Richard receives an email from his first ex-wife, and it gives him hope for a better past. Hope for a better past produces hope for a better future, not because time is a loop of roads like the LA freeways but because our minds are impressionable children, believing explanations that can’t be proved. Richard’s brother died last week, and during the past few days he’s received tender notes from his other two ex-wives as well. Dislike slips off Richard, who is made of Teflon.

I’m jealous people go on and on liking him! Today, on the phone with a friend, I told her I knew some famous artists I could invite to be guests at our Zoom conversations, except I hate them. She said she wasn’t sure if there were more famous people she hated or more people who hated her for being famous. It pleases me to tell you I have not for a moment felt anything but affection and admiration for this friend. Our bond is gentled by magic.

_____________________________________

Happenings for paid subscribers

Upcoming Zoom Conversations with guest artists include: writer and actor David Cale (November 29 from 3 to 4 EST), poet David Daniel (December 20 from 3 to 4 EST), and composer and writer Errollyn Wallen (January 17 2026 from 3 to 4 EST). To RSVP to any of these events, please email me at: lauriestone@substack.com.

To attend one event or receive one recording, with no future payment obligation, you can buy a “coffee” for $4 at ko-fi.com/lauriestone

Breakout sessions following the Zooms with guest artists

The BREAKOUT SESSION following the Zoom with David Cale is full. To RSVP for the breakout session on Sunday, December 21 from 3 to 4 EST, following the Zoom with poet David Daniel, please email me at: lauriestone@substack.com. There is a cap of 10 at each breakout. You are invited to share a piece of your own writing under 400 words, and the fee is $30.

To request recordings of past Zoom Conversations

with Steven Dunn, with Margo Jefferson and Elizabeth Kendall, with Emer Martin, with Perry Yung, with Francine Prose, and with Sophie Haigney (of The Paris Review) please email me at: lauriestone@substack.com

Working together one to one on your writing or starting and growing a Substack publication.

If you would like to book time to talk one-on-one about a project you are working on or for guidance in gaining confidence and freedom in your writing, please email me at: lauriestone@substack.com.

If you would like to book time to talk one-on-one about STARTING AND GROWING a Substack publication please email me at: lauriestone@substack.com. I can help you through the software, choosing a title, art design, and approaches to gaining readers.

Oh this was good. Especially the section about Malcolm's trial, the New Yorker, and her Jewish trial advisor. Very good. Thank you.

Brilliant piece on Malcolm. I savored every bit of your .....(I can't come up with the proper adjective here; tough? brilliant? evocative? unusual? attention-getting? Is there one word for all of these things?) writing. Brilliant, I say.