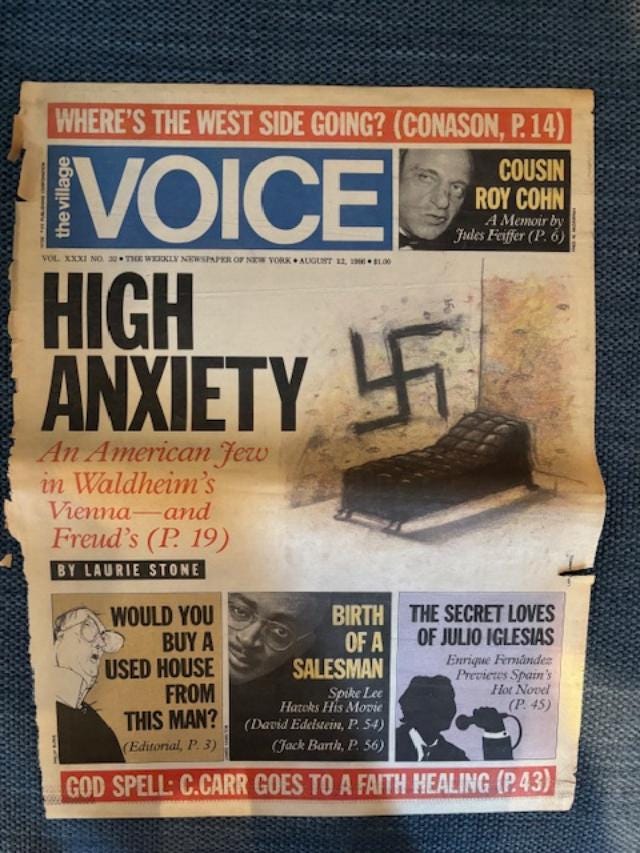

When Hitler planned to eradicate Jews from existence, he also thought he was wiping out "the feminine principle." He thought Jews embodied “the feminine principle” and that “the feminine principle” was a really bad thing you’d be justified in destroying to protect “the masculine principle” from contamination. Read on, if you would like to know more abou…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Everything is Personal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.